The primary purpose of early-stage clinical trials is to determine the recommended dose and toxicity profile of an investigational drug or multi-drug combination therapy. Since molecularly targeted agents (MTAs) and immunotherapies have toxicities that are distinct from cytotoxic chemotherapies, traditional dose escalation methods using toxicity-based endpoints may not be suitable for phase I studies of these novel agents. In this context, improved preclinical models and assessment, innovative model-based design and dose escalation strategies, patient selection, and the use of expansion cohorts can help enhance safety and optimize dosing.

Using Molecular Profiling

Defining the right patient population for a phase I oncology trial can be challenging due to complexities associated with previous treatment regimens or co-morbidities. Traditionally, phase I studies have enrolled patients with all disease types who have exhausted available, approved anti-cancer treatments.[1]

With the advent of more rapid, less costly genomic testing, we have seen an increase in biomarker-driven trials that seek to include those patients most likely to benefit from a targeted therapy and exclude those unlikely to respond. While this approach may spare non-responders from exposure to the potential toxicities of MTAs or immunotherapies, it can also contribute to delays in recruitment. It may also hinder the detection and evaluation of treatment-related adverse events due to the small number of patients treated at each investigative site.

Using Standard of Care

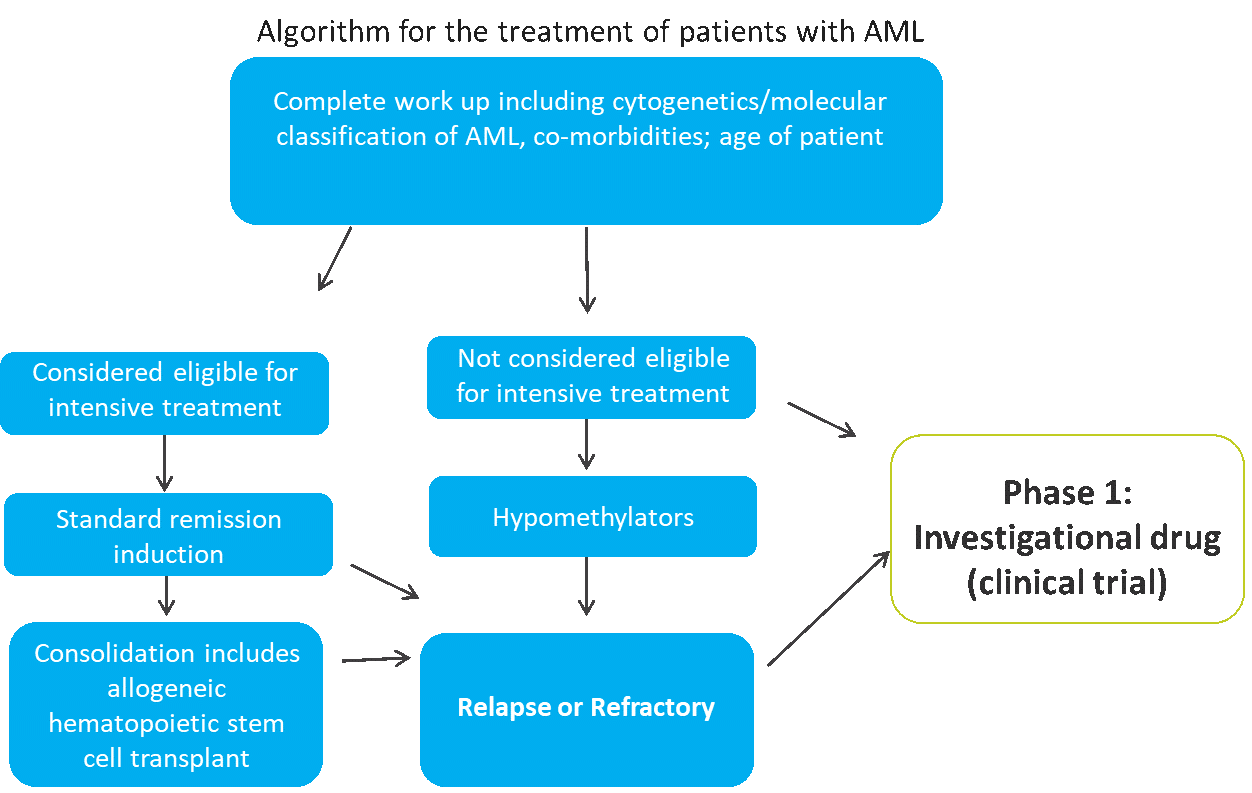

Another approach is to use the standard treatment algorithm for the indication of interest as a guideline for identifying appropriate subjects. For example, acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a therapeutic area in which standard therapy has not changed much in the past 40 years, except for the introduction of hypomethylators. Intensive treatment for AML consists of induction chemotherapy with idarubicin and cytarabine followed by consolidation treatment, which may include allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

Figure 1. Identifying Subjects for a Phase I AML Trial[2]

AML occurs with increasing frequency as patients age, and older patients are often not eligible for induction chemotherapy due to co-morbidities, bone marrow exhaustion, or other factors. The treatment algorithm for newly-diagnosed patients with AML is based on both age and fitness for intensive treatment (see Figure 1). Among older patients who are not eligible for intensive treatment, approximately 50 percent choose not to be treated.

While hypomethylators provide an option for some of these patients, their effects are typically short-lived, and patients subsequently become relapsed or refractory. These relapsed or refractory patients — along with those who are not eligible for intensive treatment — may be good candidates for a phase I study of an agent that has minimal toxicity and some evidence of efficacy.

For tumors where there are standard frontline, second-line, and third-line therapies, a novel agent could be introduced as a last-line treatment or as a third-line treatment, either alone or in combination with standard of care.

Using Healthy Volunteers

Healthy volunteers have been included in some first-in-human trials using MTAs due to their considerably lower toxicity profiles. Important factors to consider in the design of oncology trials that include healthy volunteers include:

- Careful observation of effects on major organ systems

- Early detection of adverse effects

- Limited exposure to the drug

- A conservative dosing scheme

- Immediate cessation of exposure at the first evidence of toxicity

The advantages of conducting studies in healthy volunteers include rapid enrollment, investigation of bioavailability/pharmacokinetics, metabolic profiling, dose finding, and the ability to acquire data not confounded by diseases. However, extrapolation of results from these studies to patients with cancer might be limited, and the low-dose pharmacokinetics in healthy volunteers may differ from therapeutic-dose pharmacokinetics in patients with cancer. As a result, a careful risk-benefit assessment should be made when planning trials that include healthy volunteers.[3]

With the shift toward precision oncology, trial eligibility should, if possible, be based on an individualized approach. As patient selection in phase I trials can have far-reaching effects that impact later stage clinical studies, sponsors should carefully apply a data-driven approach to defining their target population. For more information, check out our webinar Driving Product Development and Finding the Fast Track in Early-Phase Oncology Programs.

[1] Cook N, et al. Early phase clinical trials to identify optimal dosing and safety. Molecular Oncology 2015;9:997-1007.

[2] Ossenkoppele G and Löwenberg B. How I treat the older patient with acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 2015;125(5):767-774.

[3] Gupta P, Gupta V, Gupta YK. Phase I clinical trials of anticancer drugs in healthy volunteers: need for clinical consideration. Indian J Pharmacol [serial online] 2012.