Remarkable progress has been made in our understanding of the genomics of pediatric cancers, and these advancements have led to the recognition that products being studied for use in adult cancer indications may have health benefits for pediatric patients. By closing the orphan drug exemption loophole and enabling earlier discussions with the FDA, the Research to Accelerate Cures and Equity (RACE) for Children Act has the potential to accelerate the development of novel treatment options for children with cancer.

Submitting an initial pediatric study plan

Per the RACE for Children Act, molecularly targeted pediatric cancer investigations should utilize appropriate formulations to yield clinically meaningful study data regarding dosing, safety, and preliminary efficacy for informing potential pediatric labeling.[1] The critical first step in complying with the RACE for Children Act is submitting an initial pediatric study plan (iPSP) outlining a proposed timeline and design of pediatric studies with each Investigational New Drug that falls within the scope of this legislation.

Typically, an iPSP must be submitted no later than 60 days after the End-of-Phase 2 (EOP2) meeting. Sponsors may want to consider drafting the iPSP after the Phase 2 studies have been completed and before or at the EOP2 meeting to allow for strategic discussions around endpoint selection for both the adult and pediatric studies. If the sponsor is seeking accelerated approval with a Phase 2 study, then the iPSP should be submitted after the End-of-Phase 1 (EOP1). If the initial IND includes a phase 3 study, the iPSP should be submitted at the time of the IND submission.

The FDA guidance Pediatric Study Plans: Content of and Process for Submitting Initial Pediatric Study Plans and Amended Initial Study Plans [PDF] outlines the timing and expected contents of an iPSP. Key components of the iPSP are:[2]

- An overview of the disease in the pediatric population

- An overview of the investigative product

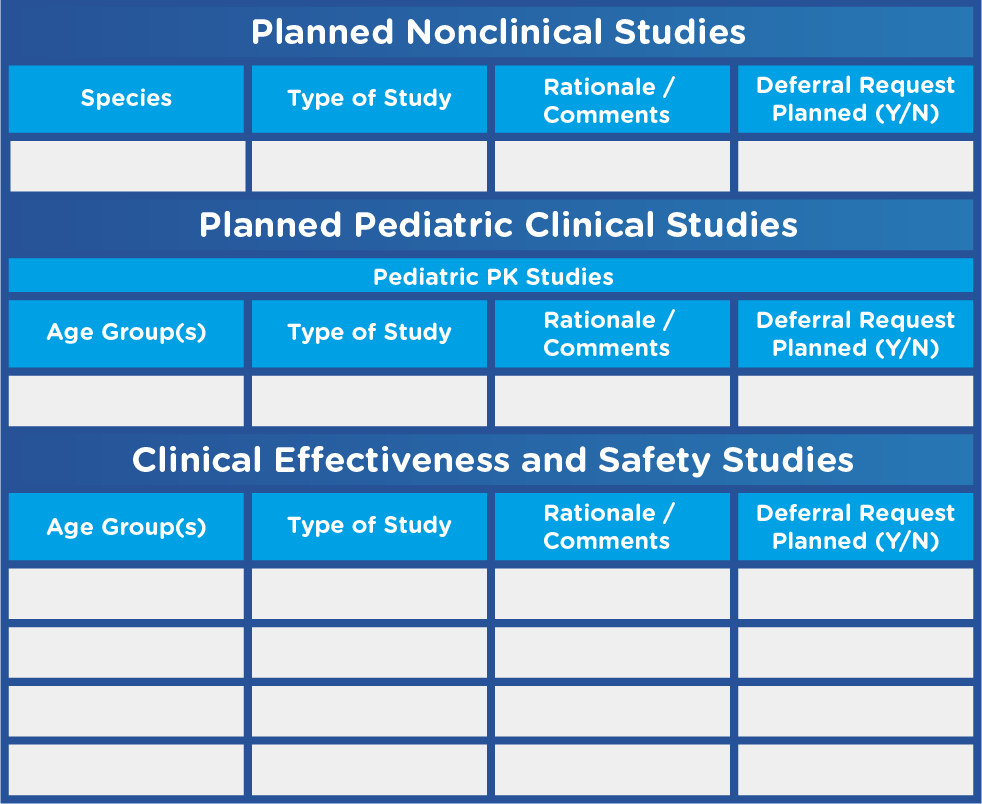

- A tabular summary of all planned nonclinical and clinical studies (see Figure 1)

- Details of any pediatric-specific formulation development plans for all pediatric age groups that will be studied

- A brief summary of data from relevant nonclinical studies or, if the existing data are not sufficient, a description of the nonclinical studies to be conducted

- A brief summary of clinical data supporting the design and/or initiation of pediatric studies

- An outline of planned clinical studies, including pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) studies and studies of safety and efficacy

- A development timeline

Figure 1. Sample Tabular Summary Template

Adapted from U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Pediatric Study Plans: Content of and Process for Submitting Initial Pediatric Study Plans and Amended Initial Study Plans.

Key factors to keep in mind when developing an iPSP include:

- Studies will need to be conducted in each age group in which the investigational product is relevant

- Different pediatric age groups may be considered separate labeling indications and may require different product formulations

- Pediatric trials must be carefully designed to meet the expectations of a range of stakeholders, from regulators and investigators to children and their caregivers

Taking action

While the RACE for Children Act more closely aligns U.S. pediatric requirements for oncology products with EU requirements, there are subtle but important differences between the regulations. In the EU, for example, the pediatric investigative plan (PIP) must be submitted no later than upon completion of the human pharmacokinetic (PK) studies unless otherwise justified. In addition, all elements of the PIP are binding, and any modifications must be reviewed and approved by the European Medicines Agency. Moreover, a marketing authorization application to the EMA for a new product/variation or extension must include verification that the pediatric development has been conducted in line with the timelines and plans outlined in the PIP.

The need to plan for – and ultimately conduct – pediatric oncology trials may be daunting. With the shift from indication to molecular target, sponsors face the challenge of reassessing and prioritizing their pipelines. As many products have a common molecular target, clinical trials may become increasingly competitive as studies vie for the same small pool of patients. Specialty pharma and biotech companies without pediatric experience may want to explore industry collaborations or partnerships with contract research organizations (CROs) that have expertise at the intersection of pediatrics and oncology. Learn more by downloading our white paper, The Science and Art of Conducting Clinical Trial Feasibility in Rare Disease and Pediatric Studies.