Last Updated: January 6, 2026, 10 am UTC

While clinical trials for medical devices have many similarities to those for pharmaceuticals, the regulatory evaluation of devices is distinct from that of drugs – and there are critical differences in the way the device trials are designed and executed.

Here are a few of the key differences:

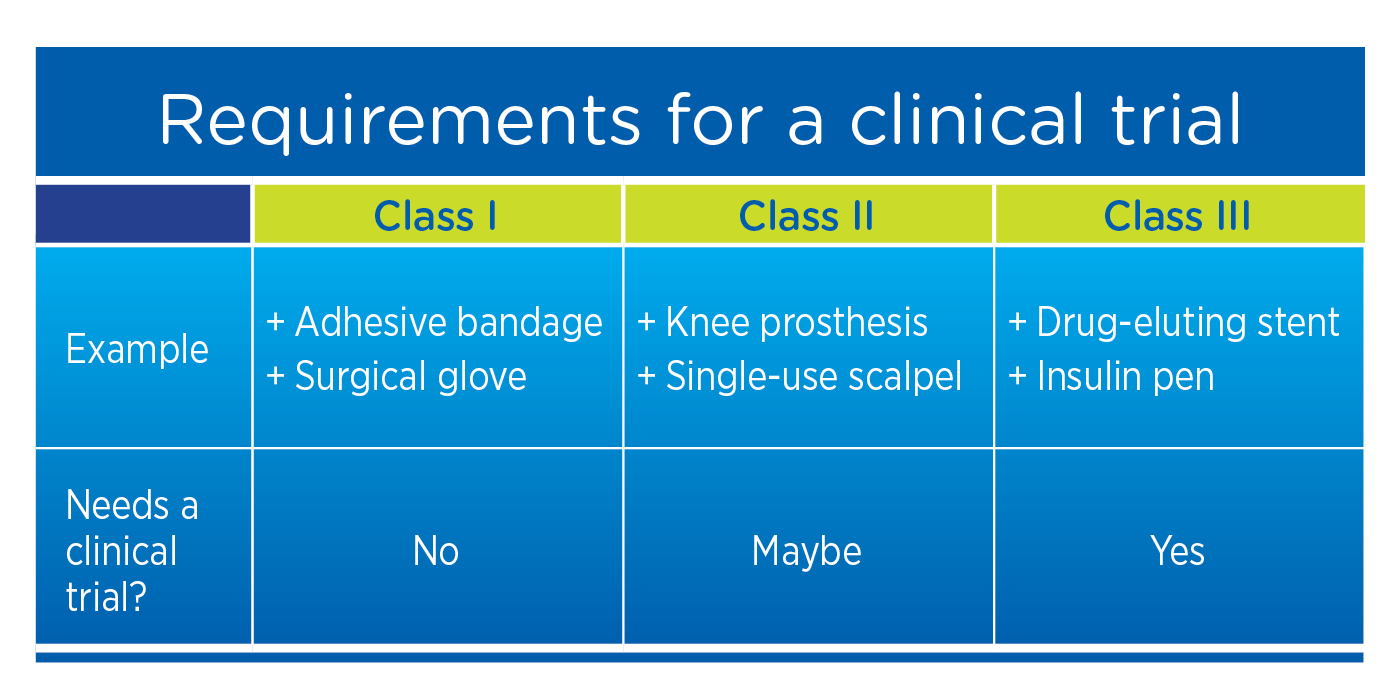

- Requirement for a clinical trial

When studying new drugs, a clinical trial is required. However, when studying medical devices, clinical trials may not be required, depending on the risk stratification (or class) of the device. In the U.S., all Class III (and some Class II) devices require a clinical trial. In the EU, even Class I devices require clinical evidence demonstrating that the level of device effectiveness consistently and accurately meets requirements for the labeled application.

In the EU, even Class I devices require clinical evidence demonstrating that the level of device effectiveness consistently and accurately meets requirements for the labeled application.

2. Population studied

Early-phase clinical trials for new drugs typically include a small number of healthy subjects. However, for medical devices – particularly those that require a surgical implant – it may not be appropriate to insert the device into healthy subjects. Instead, a device trial may be initiated in a small pilot population with the disease or condition under study before moving into the larger pivotal populations. Generally, the total number needed to treat to demonstrate safety and effectiveness in a device trial is in the hundreds rather than the thousands needed in drug trials.

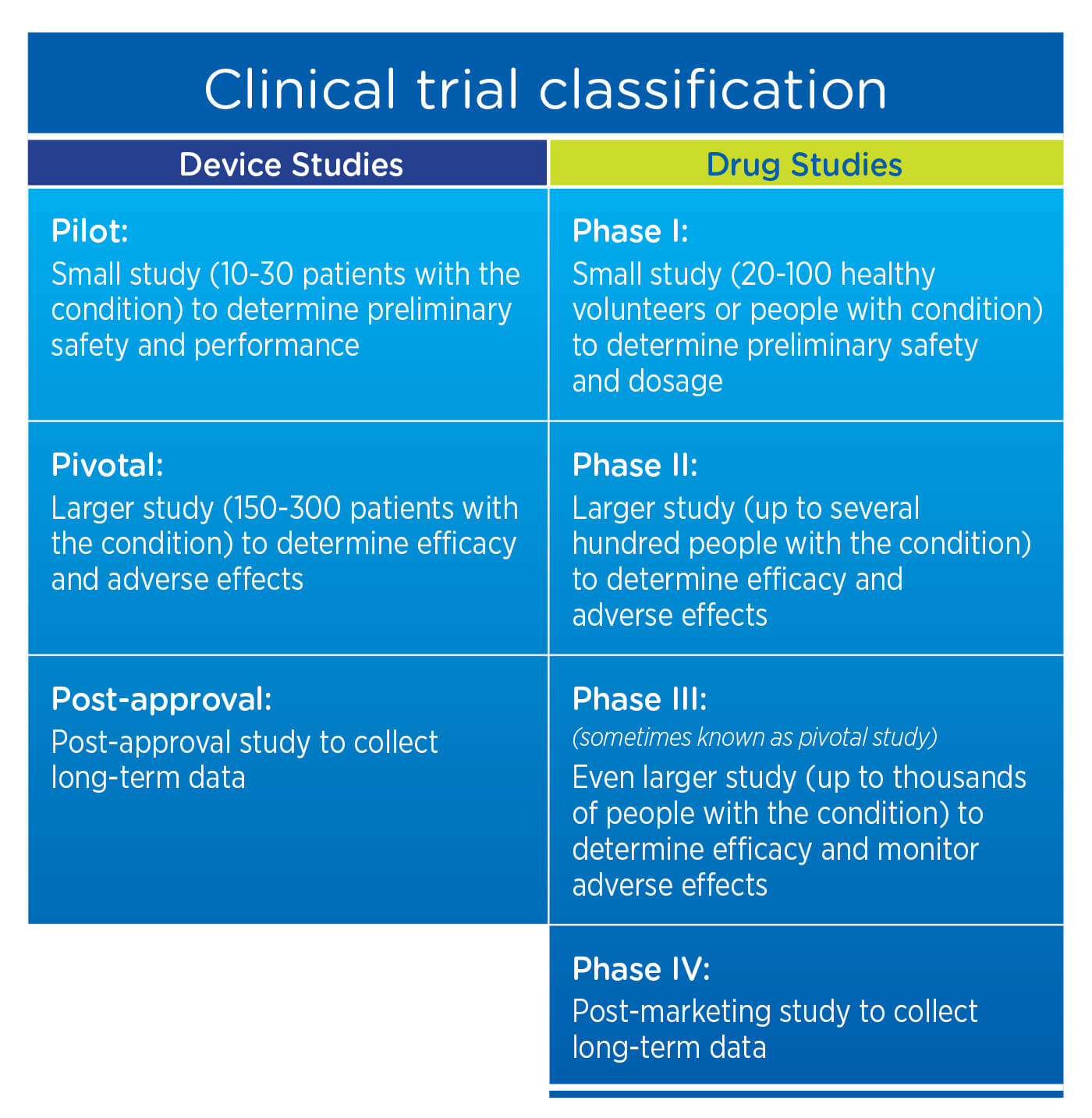

3. Clinical trial classification

For drug studies, post-marketing studies are typically considered Phase IV Studies. For device studies, the requirement for long-term data is generally satisfied with a Post-Approval Study.

4. Clinical trial design

For medical device studies, it may be unethical (or even impossible) to use a placebo. As an example, if the device under study is a prosthesis for total knee arthroplasty, the subject could not undergo a sham operation and have treatment withheld. It may also be difficult or impossible to conduct double-blind device trials. In addition, medical device trials are likely to include at least one imaging modality that enables the sponsor to see the device and ensure that it is functioning as intended.

5. Safety reporting

The safety reporting requirements for devices differ from those for drugs. For drugs, sponsors are only required to report serious adverse events (SAEs) that may reasonably be regarded as caused by, or likely caused by, the drug. For devices, manufacturers are required to report all SAEs, even if they are not directly related to the device or the procedure in which the device is used. This requirement applies not just to implantables, but also to in vitro devices and diagnostics which are not used directly by the patient. If a participant in an in vitro diagnostic trial experiences a health condition that is not related to the device, that condition must still be reported.

6. Regulatory requirements

While sponsors of medical device trials are not required to submit an Investigational New Drug Application (IND, per 21 CFR Part 312), they are subject to 21 CFR Part 812, Investigational Device Exemptions. Notably, the Investigational Device Exemption (IDE) requires hands-on device training for investigator and site staff, in addition to protocol training, because the efficacy and safety of the device may be highly dependent upon physician technique.

Sponsors should also keep in mind differences between the regulatory landscape for medical devices in the U.S. and the EU. One of the primary differences is the use of notified bodies in the EU to perform conformity assessments and enforce regulation through unannounced inspections of manufacturing processes.

On May 5, 2017, the European Parliament published new regulations for medical devices and in vitro diagnostics which introduce:[1]

- An expanded definition of medical devices to include devices with purposes related to the prediction and prognosis of disease

- Stricter rules and requirements for clinical evaluation and clinical investigation

- EUDAMED, a comprehensive EU medical device database that will contain information on the lifecycle of all products available on the EU market

- A new device identification system based on a unique device identifier (UDI) that will enable easier traceability of medical devices

- An implant card for patients with implanted medical devices, which will contain the name of the device along with the serial number, batch code, UDI, device model, and relevant warnings and precautions

- An EU-wide coordinated procedure for the authorization of multi-center clinical studies on medical devices

- A reinforced requirement for manufacturers to collect data about the real-life use of their devices

- Improved coordination among Member States in the areas of vigilance and market surveillance

By developing a deep understanding of both the clinical development process and regulatory landscape for medical devices, sponsors can more efficiently and proactively build out a strategy for bringing their devices to market to help the patients who need them.

[1] European Commission. New EU rules to ensure safety of medical devices. Brussels, April 5, 2017. Available at https://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_MEMO-17-848_en.htm.

Perspectives Blog

Perspectives Blog